I Wanted to “Become One” With My Romantic Partner. Then Someone Actually Started Living Inside Me.

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

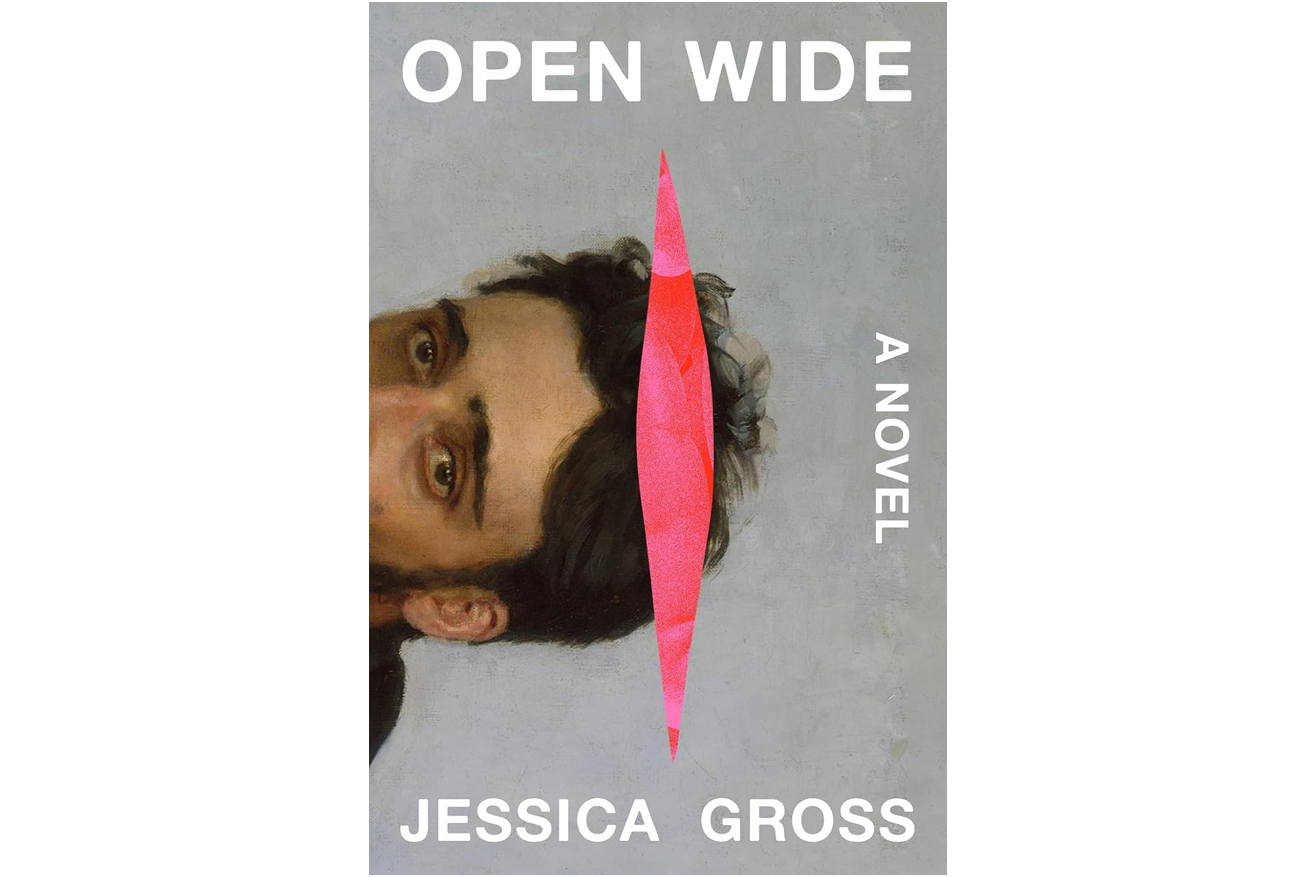

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">When I started writing my new novel, Open Wide , in 2019, I was a single woman in her early 30s who lived in New York City. Over the next few years, I fell in love, moved to West Texas, and got married. But the gap between when I finished the manuscript, in September of 2023, and the book's publication this week has seen the biggest change I've ever experienced: I became a mother.

I imagine that for every author, the time between when a book sells (for me, January of 2024) and when it's published sees personal evolution that's hard to assimilate. Promoting a book written by a former version of yourself—and even revising it with your editors in the months leading up to publication—can feel like squeezing into a too-small outfit from your youth. In my case, the outfit was a novel about Olive, a 33-year-old radio host who becomes so obsessed with her boyfriend that she can't stand the thought of being separate from him; if that makes you think Uh-oh, boundary issues , you're on the right track regarding Olive's novel solution.

The person who had written this book, which focuses on the early stages of romantic love, didn't know what it was like for a small person to emerge from my vagina who had almost no capacities and was entirely dependent on me. When I surfaced from the haze of early motherhood for short stretches, usually while my daughter was sleeping, and frantically tried to apply my completely altered brain to the task of revising my book, it felt as if I were trying to reaccess my previous self's interests, her preoccupations, even her language.

I had written the bulk of the novel when my main personal project had been navigating the boundary confusions brought up by my first romantic relationship in years, and the most serious one by far. On the page, via fiction, I wrestled with the issue that was plaguing me in life: How separate are we supposed to be from our partners, who are supposedly our “other halves”? What should I do with my desire to melt into my partner and be freed from the loneliness that singular personhood entails?

Once I was revising the book, these questions felt quaint. I was trying to keep a baby alive. I was consumed with how to stop staring bug-eyed at my daughter the entire night long, making sure she was still breathing. I was wrestling with the crushing terror of handling a level of adult responsibility I had never experienced before. whereas in prior years I'd longed to merge my identity with my boyfriend cum husband's, now I lacked a sense of self outside my daughter. She was now my purpose, and I wanted to submit to being her vessel, even as it was the greatest challenge I'd ever faced. Why was I trying to reenter the headspace of a young romantic when a fragile life was on the line? The untested person who'd written that novel hadn't even known what it was like to be pregnant!

Or had she?

By the time I received a positive pregnancy test, I had given my protagonist an avenue for merging with her partner that my very real life didn't offer up: Rather than simply trying to spiritually merge with Theo, she would literally do so, by unzipping his body while he was sleeping and nestling herself inside. Via this ability, I transmuted my own relationship confusions to the supernatural realm. Moreover, later events in the novel (which I won't spoil here) even more accurately predict what it is like to house another body. The fetus inside is in you, practically is you—but at the same time, you can't access their thoughts, their feelings, even their personalities. How had my nonpregnant self so aptly conveyed the experience of having an entire other person inside of oneself?

Was it because I, myself, had been a fetus once? Or (and?) because the desire I struggled with in my relationship—to become one with my partner—was an infantile one?

As I dove, by requirement, into edits of my book as a mother, I started to realize that maybe my novel wasn't so irrelevant to my new life after all. Not only had I known all about what it was like to house a body inside of your own and gotten it onto the page with startling accuracy—especially that paradoxical combination of unparalleled closeness and total mystery—but the issues I'd struggled with in my relationship presaged issues I would struggle with as a mother.

If I thought I needed to work through my desire to be one with my husband, that was nothing compared to the wrenching sadness I felt as I considered weaning my daughter. This little person had been one with me, and as challenging as I had found those early months of motherhood, I had grown to love and even depend on her physical closeness. I loved nursing her throughout the day and night. I loved sleeping with her curled against my side. I loved putting her in the carrier and going about our day together, her little body pressed close to mine.

She loved it for a time too. But, like all children, as she grew, she craved more freedom. She began to crawl, and then to walk on her knees. She started moving around more in the bed, looking for a little space from me. Eventually I had to concede that breastfeeding her any time of day or night wasn't helping her—it was holding her back. When I began to wean her, she started to eat more real food. A day short of 19 months old, she started to walk on her own.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

My novel wasn't, it turned out, written by a person with whom I had nothing in common any longer: It was written by a me with issues that I am still working through. In retrospect, this makes total sense. The issues I grappled with in my romantic relationship were brought up by my own upbringing, which of course also fueled my struggle to handle gracefully my daughter's increasing independence.

Now, I think that it wasn't so much that I'd wanted to merge with my husband as that I'd wanted to go back to the time when I'd been one with my own mother. Maybe this lonely longing to crawl inside another person—to be, essentially, a fetus again—will hover like a ghost around my relationships forever. As I'm writing this piece, I am dragging my feet on stopping nursing my 20-month-old daughter to sleep—that one final feed that's keeping our breastfeeding connection alive—and on moving her out of our bed into her own room.

But having Open Wide as a touchstone helps me remember that when we refuse to embrace our separate personhoods, we can stunt growth, both others' and our own. This desire to merge may never leave me. But I can treat it as the little frenemy of a ghost that it is; it doesn't need to be heeded. Seeing where it can lead is what fiction is for.